This article is contributed by Jason Dirkham.

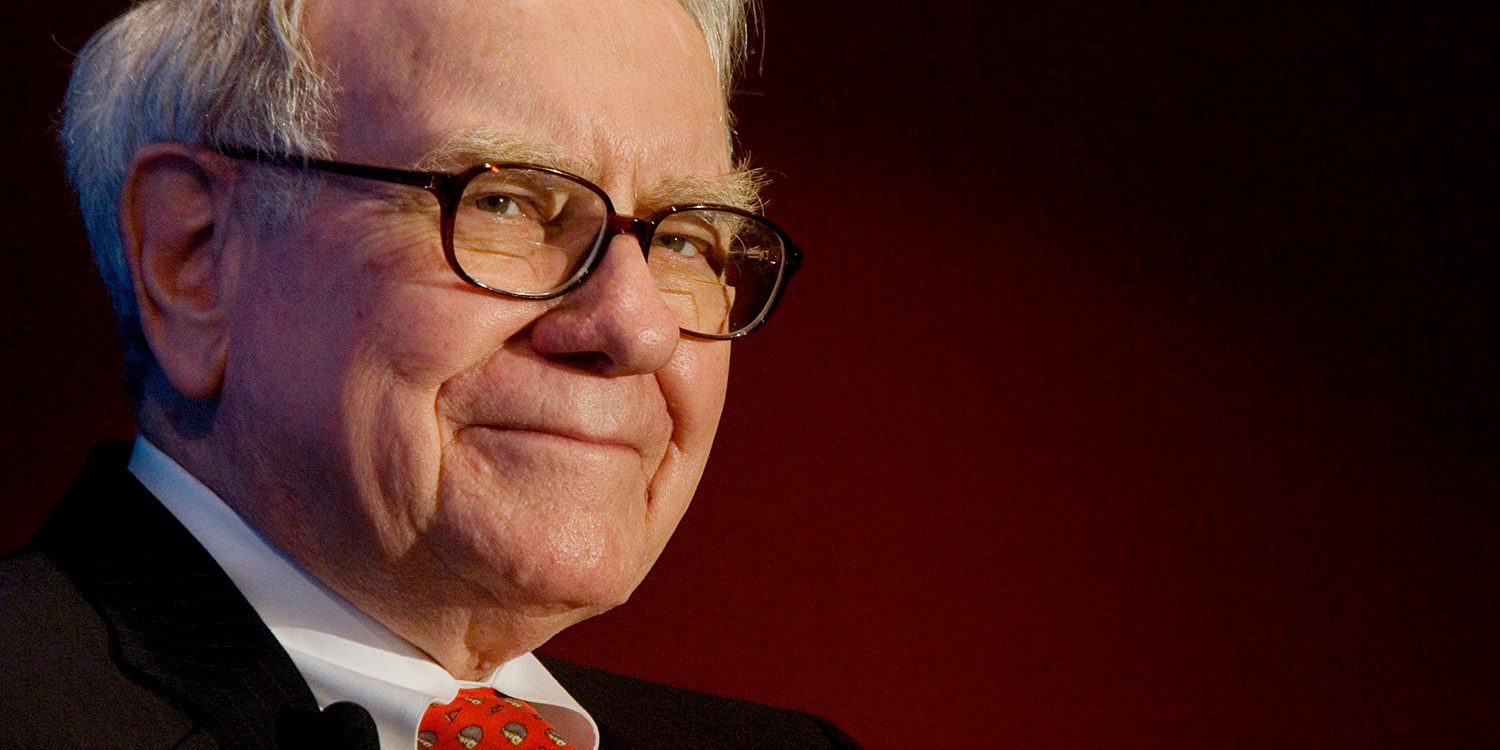

Warren Buffett is the most celebrated investor of modern times, and rightly so. The man has amassed a corporate fortune of more than $500 billion and a personal portfolio well above $70 billion. Buffett is an understated character who never brags about his achievements. It’s all part of his charm. He still lives in the same small house in Omaha, Nebraska that he lived in during his 30s.

Over the years, the reasons for Buffett’s success have remained something of a mystery. How is it that a man sitting in an office could beat the market, year after year, by considerable amounts? According to mainstream economic thinking, that wasn’t possible. He was either a genius, or it was a fluke. Beating the market just wasn’t allowed according to conventional economic models.

The efficient market hypothesis says that the price of an asset reflects all information available to the market at a given point in time. Prices, therefore, reflect the underlying securities (like stocks and shares) and always do. The only reason prices ever change is that new information arrives and the market responds, updating prices through a series of trades. Conventional economic thinking, therefore, didn’t leave any room for a character like Buffett. It just wasn’t possible to beat the market as consistently as he did unless he had access to secret sources of information.

Mainstream finance didn’t have much of an answer to the example of people like Buffett. The best that they could come up with was that in any population of investors, some would have lucky breaks while others will crash and burn. But the odds that somebody would be able to generate 20 percent average annual returns for decades on end was just so unlikely that you wouldn’t expect an investor like Buffett to emerge even once in a million years.

In the 1970s, economists started to explore whether things other than market risk drove expected returns from stocks. Up until that point, economists had argued that the only reason why people buy stocks instead of government bonds is that stocks offer a higher expected rate of return. The higher rate of return compensates them for the risk that they take when they buy a share in a company. Otherwise, they’d invest in risk-free government bonds and receive the guaranteed coupon.

However, economists at the Chicago school, particularly Eugene Fama, began to question the notion that price volatility alone determined risk. In their view, other fundamental sources of risk made a difference too. Using some intelligent statistics, Fama and colleague Kenneth French showed that while market volatility could explain some of the expected returns of the market, other factors were important too, such as the size of the firm (with small firms being more risky than large) and value (with firms with a lower price to book ratio doing better). When Fama and French included these alternative risk premia in their models, they soon discovered that they could explain expected returns much better than if they just used the traditional market risk measure (often called beta). Their regression model showed that there was actually more than one beta, which could explain variations in expected returns. It was a significant breakthrough.

The statistics aside, it also made a lot more sense. Small companies have far more scope to grow than larger companies, but they are also more prone to dying out. The risk of a small company is higher, but so too is its reward. Small companies can grow at triple-figure growth rates while large companies, for the most part, cannot.

Value companies also tend to perform better than growth stocks in the long term too. Again, this has to do with the fact that if a company is undervalued today, then it indicates that it’s on a bit of a down and out and that the market doesn’t expect it to remain profitable for the long term (at least not compared to growth stocks). Investors who buy these kinds of companies, therefore, take on additional risk. People want to be compensated for the fact that a company is cheap and not at all sexy. It’s the difference between a value company like Intel (suffering from the end of Moore’s Law and overwhelming competition from AMD), and a sexy growth stock like Amazon, a company many believe is in a great position to double its value over the coming decade.

According to the theory, if an investor invests in risky stocks, small stocks and value stocks then, over the long run, that investor will make higher expected average annual returns than an investor who plays it safe. When Warren Buffett began his investing career, he didn’t have the advantage of being able to go out and read papers by economists, like Fama and French. Multi-factor investing ideas hadn’t yet been developed. Instead, the Oracle of Omaha had to go out and work it out himself, almost intuitively. Fama and French only published their three-factor model in the early 1990s. Buffett had been doing his own version of it for decades before that.

Should Your Business Follow The Factor Investing Model Today?

The question for budding investors, therefore, is should you adopt a multi-factor portfolio going forward? The answer to that is probably yes, especially if you’re a retail investor. The cool thing about these multi-factor investing strategies is that they tend to diversify risk better. Often, many of the factors, like size, value, profitability, and momentum, are uncorrelated with each other, not only leading to higher expected returns but also less volatility too.

Building your own factor investing model is a bit of a challenge. Buffett based his career around it. Doing it from scratch means learning some pretty tough statistics. The good news, however, is that you don’t have to become a stats whizz to do it anymore. You’ve got two options: you can either approach a mutual fund that does factor investing professionally, allocating stocks and shares according to a formula. Or you can buy an ETF which does something similar but is not professionally managed. Usually, mutual funds will charge a high percentage fee, often between 1.5 and 2.5 percent per year, while ETFs are much cheaper, generally under 0.5 percent per year.

The most important thing is to avoid the error of picking individual stocks unless you have a lot of confidence that you know better than the market. Remember, the professional economists who came up with this theory believed that markets are efficient and that it’s just not possible to beat other people consistently. Eventually, the market learns and adapts to whatever strategy you try to implement to beat it. The reason Buffett did so well wasn’t that he was some kind of business prophet, able to see which companies would be successful, and which wouldn’t: it was that he understood different types of risk and used them to his advantage. When you analyze Buffett’s past performance taking all the factors into account, his lead over the market evaporates. Not even Buffett could generate true alpha, so it’s unlikely that you can either.

So what have we learned? What we’ve discovered is that playing the market probably isn’t a good idea. The best strategy is to put the excess money your business generates into a tracker fund and then follow the market up as it inevitably rises over time. Buffett discovered factor investing through intuition, but given the knowledge, tools, and products available today, there are no reasons why a modern, small scale investor can’t emulate the great man himself.

This article is contributed by Jason Dirkham.